A Look Inside the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center

The Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (“MSK”) was established in 2006. The Geoffrey Beene Foundation (and until 2018, Geoffrey Beene LLC), has funded over 160 separate new revolutionary research initiatives across all cancers to develop new treatments for cancer patients.

G. Thompson (“Tom”) Hutton, the Trustee of the Geoffrey Beene Foundation and President and CEO of Geoffrey Beene, LLC, (until 2018) founded the creation of the Center primarily for the purpose of funding new revolutionary research leading to new treatments for cancer patients and orchestrated the activities to build and support this ambitious research initiative. “The hallmark of the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center at MSK is its focus on revolutionary new research approaches across a variety of cancers, strategies that will lead to prevention through improved diagnostics and enhanced quality of life treatments toward the ultimate goal of making cancer a more manageable and perhaps one day, a curable disease” said Harold Varmus, M.D. Nobel Laureate and former CEO of MSK and former Director of the National Institute of Health and the National Cancer Institute.

Since its creation, the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center has served as the focal point at MSK for an array of projects, aimed at translating works at the cellular level into revolutionary new research approaches to preventing, diagnosing, and treating the disease. It brings together researchers and physicians from two complementary areas: the Cancer Biology and Genetics Program, based in the Sloan Kettering Institute (SKI), which studies the genetic and biochemical events that trigger the transformation of normal cells into cancerous ones, and the Memorial Hospital-based Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program, which pursues new insights into the molecular mechanisms of cancer from the perspective of clinical oncology.

“The Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center has helped galvanize our efforts to gain new insights into cancer and to apply that knowledge to the development of more effective strategies for patient care,” said Harold Varmus. “We are especially grateful to Tom Hutton and his colleagues at Geoffrey Beene for recognizing the significance of the work being done here” said Harold Varmus.

The Geoffrey Beene Foundation supports advanced new research initiatives spanning the entire range of translational research, funding core research labs, the establishment of senior and junior faculty chairs, graduate fellowships, the annual Geoffrey Beene Symposium, and the annual Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Retreat. The Center provides support for the Geoffrey Beene Translational Oncology Core, directed by Dr. Charles Sawyers. The core performs genomic analyses of clinical material by applying state of the art genome-scale molecular profiling technologies.

The Center also provides support for the Microchemistry and Proteomics Core Facility and Genomics Core Facility, both of which are aimed at significantly augmenting Memorial Sloan Kettering’s capacity for translational cancer research in genomics.

Since 2006, 160 grants have been awarded and 18 proposals for shared resources have been funded. Each grant funds initial-stage research and is renewed for a second year. Each year the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center’s Executive Committee reviews submissions of innovative research proposals. This highly competitive review process awards grants to the most compelling and profound ideas proposed by researchers from the MSK community. After completion of the funded project, grant recipients have gone on to develop their novel ideas and apply for further grants from external sources. Since 2006, for every dollar of direct support from the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center, grant awardees received an additional $1.67 in follow-up funding from external sources based on the early-stage ideas supported by the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center. Throughout the year, the Center sponsors several events that foster interactions between clinicians and basic researchers in an effort to encourage translational research relationships. This is the thirteenth annual retreat attended by CBG, HOPP, and faculty members across the institution.

Oversight of The Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center is provided by an Executive Committee. Scott Lowe, PhD, Member in the Cancer Biology and Genetics Program (CBG) serves as chair to the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center. David Solit, MD, Director of the Center for Molecular Oncology and Member of the Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program (HOPP) was appointed Geoffrey Beene Senior Chair in 2013.

Elizabeth Kantor, PhD, MPH, Associate Attending in Epidemiology; Adrienne Boire MD, Associate Attending in Epidemiology-Biostatistics; Nikolaus Schultz, PhD, Associate Attending in Epidemiology-Biostatistics; and Daniel Bachovchin, PhD, chemical biologist are currently appointed to Geoffrey Beene Junior Faculty Chairs.

Andrea Ventura, Member in CBG, Ping Chi, MD, PhD, Associate Member in HOPP; Alan Ho, MD, Associate Attending in Medicine; and Joseph Sun, PhD, Member in the Immunology Program have previously held the Geoffrey Beene Jr. Chair.

Since the establishment of the Center, 46 Geoffrey Beene Graduate Fellowships have been awarded. Support has also been provided for the Geoffrey Beene Translational Research Core Facility, the Microchemistry and Proteomics Core Facility, the Genomics Core Facility, High-Throughput Drug Screening Facility, and the RNAi Core Facility, and the Antitumor Assessment Core.

Congratulations to Dr. James Allison, one of the founding board members of the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center for his groundbreaking immunology research leading to checkpoint inhibitors and being awarded the Noble Prize on October 1, 2018.

With the Geoffrey Beene Foundation’s support, the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center intends to jointly host in New York City another highly successful Geoffrey Beene and Nature Conference. The previous conference entitled: The Tumor Cell: Plasticity, Progression and Therapy was held on March 3-6, 2019. The organizers were Barbara Marte (Nature, UK), Ross Levine (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, USA), Scott Lowe (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, USA), Dana Pe’er (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, USA), Sarah Seton-Rogers (Nature Reviews Cancer, UK), Alexia-Ileana Zaromytidou (Nature Cell Biology, UK). To find out more (click here)

The Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center Program for Precision Disease Modeling Cancer researchers require disease models that can be studied in the laboratory in order to understand cancer and deliver therapies to cancer patients. One of the activities of the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center is providing support to researchers at MSKCC in developing new and accurate cancer models, using these to understand how the genetic changes that contribute to cancer work, and how they can be targeted by new cancer drugs. This support has been provided through two broad mechanisms. On the one hand, the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center provides funds for specific research projects conducted by MSKCC investigators, some of which are highlighted below. On the other hand, it has provided funds for technical support and infrastructure to produce “precision disease models” for testing new cancer drugs. The latter effort provided funding which enabled a broad institutional wide effort for the development of precision disease models and led to the awarding of a $10 million grant to MSKCC from the National Institute of Health to develop a pilot center that will serve as a model for nation-wide efforts to improve the generation and use of accurate models of human disease.

Highlighted Stories from the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center at MSK

Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center

Robert Benezra, PhD Member of the Cancer Biology and Genetics Program Deputy Director for Core Technologies at MSK Laura and Christopher Pucillo Chair in Metastasis Research

Tackling Liver Inflammation and Cancer Risk

High dietary fat intake can lead to a harmful inflammatory response in the liver, known as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a condition that significantly increases the risk of developing liver cancer. In laboratory studies, researchers have observed that high-fat, high-fructose diets can trigger fat accumulation in the liver, followed by inflammation and reduced liver function. However, the exact mechanisms behind this process have been unclear. Dr. Benezra has made significant strides in understanding and addressing this challenge. His team found that when fat accumulates in the liver, a protein known as ID1 is elevated in Kupffer cells, a specialized immune cell in the liver. By globally knocking out the ID1 gene, they found near-complete protection against the inflammatory response in NASH models and are pursuing additional studies to further define the underlying mechanisms.

This research offers hope for new therapeutic strategies to combat NASH and reduce the risk of liver cancer. By targeting the ID1 protein in liver immune cells, it may be possible to prevent or reverse the harmful inflammatory response caused by high-fat diets. This could lead to more effective treatments for patients suffering from NASH and related liver conditions, ultimately improving patient outcomes and quality of life.

Lydia Finley, PhD Member of the Cell Biology Program Geoffrey Beene Junior Faculty Chair

Targeting Cancer Cell Metabolism to Stop Lung Cancer

Dr. Finley’s current research focuses on understanding how different metabolic pathways — the chemical reactions inside cells that keep them alive and functioning — support various cancer cell populations in lung adenocarcinoma, a common and deadly type of lung cancer. Working in collaboration with Tuomas Tammela, MD, PhD, of the Cancer Biology and Genetics Program, the research team discovered that these lung cancer cells use both standard and alternative versions of a key metabolic pathway known as the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. By manipulating these cycles, they found that they could alter the diversity and growth of cancer cells. Their findings suggest that targeting the alternative TCA cycle could eliminate highly adaptable and treatment-resistant cancer cells, potentially halting tumor progression. These advances have laid the groundwork for a successful R01 grant application and will form the basis of a future publication.

This highly successful collaboration would not have been possible without the transformative support of the Geoffrey Beene Foundation. Dr. Tammela’s and Dr. Finley’s research indicates that targeting specific metabolic pathways in cancer cells can alter their behavior and potentially improve treatment outcomes. By understanding how different TCA cycle configurations support cancer cell diversity and growth, researchers and clinicians can develop more effective therapies that target the most resilient cancer cells. This approach could lead to better strategies for managing lung adenocarcinoma and improving patient survival rates.

Elizabeth Kantor, PhD, MPH Associate Attending Epidemiologist Geoffrey Beene Junior Faculty Chair

Optimizing Treatment With Chemotherapy

Dr. Kantor is building the Optimal Breast Cancer Chemotherapy Dosing (OBCD) Study, a cohort of over 34,000 people treated for breast cancer at Kaiser Permanente Northern California or Kaiser Permanente Washington. This work is primarily focused on understanding the role of chemotherapy dosing in patients with obesity, and how these dose reductions may ultimately impact patient outcomes. As part of this work, the OBCD team has developed methodologic approaches for leveraging rich electronic health record data, including identification of the specific intended regimen, while also broadly describing variations in treatment. Ultimately, it is our hope that findings from the OBCD Study may help optimize treatment strategies, improving survival rates and quality of life for patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Scott Lowe, PhD Chair of the Cancer Biology and Genetics Program Chair of the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center Geoffrey Beene Chair

Developing New Applications for CAR T Therapy

A groundbreaking study led by Dr. Lowe demonstrates the potential of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells to treat aging-related diseases by targeting senescent cells, or damaged cells that drive chronic inflammation and tissue dysfunction. The team — which includes MSK investigators Michel Sadelain, MD, PhD, Stephen and Barbara Friedman Chair; Ross Levine, MD, Laurence Joseph Dineen Chair in Leukemia Research with Special Emphasis on Leukemia in Children and Young People; Gerstner Sloan Kettering graduate student Inés Fernández Maestre; and former MSK student Corina Amor Vegas, MD, PhD — engineered CAR T cells to recognize and eliminate senescent cells by targeting a molecule called urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR), found on their surface. In mouse models, this approach improved metabolic function, reduced inflammation, and even enhanced physical endurance in older mice. Notably, a single treatment in young, healthy mice prevented metabolic decline as they aged, showcasing the long-term benefits of this therapy. Unlike small-molecule therapies, which often lack precision and require repeated administration, CAR T cells provide durable, targeted effects. These findings, published in Nature Aging, highlight the potential of CAR T cells to extend quality of life by addressing underlying conditions such as metabolic syndrome.

The research underscores the versatility of CAR T technology, which was originally developed for cancer treatment. The team envisions further refinement and clinical translation of this therapy to combat aging-related diseases. By leveraging innovative immune cell engineering, the study paves the way for transformative treatments that could improve quality of life and opens new possibilities for regenerative medicine.

Scott Lowe, PhD

Chair, Cancer Biology & Genetics Program

Chair, Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center

CAR T cells beyond cancer: senescence related diseases

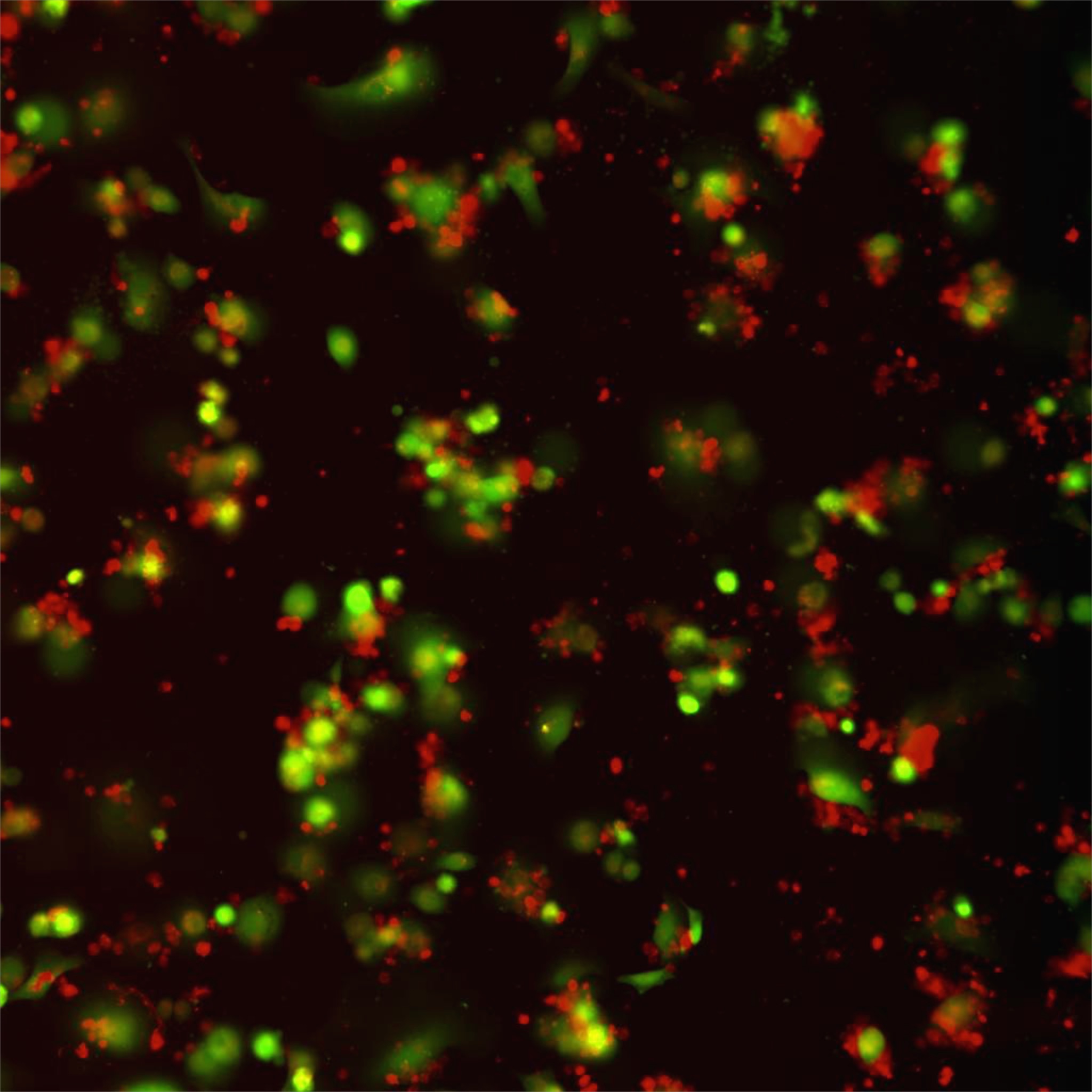

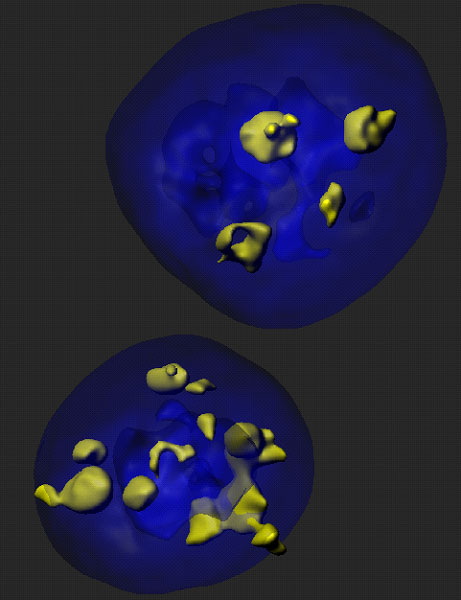

T cells genetically engineered to express chimeric antigen receptors (CAR T cells) are able to effectively target the antigen expressing target cells. Thus, CAR T cells targeting the B cell protein CD19, which were developed among others by the group of Michel Sadelain at MSKCC, have shown remarkable efficacy in patients with refractory B-cell malignancies. The application of CAR T cells beyond cancer however, was not explored. Our new research set to study whether CAR T cells could also be harnessed to eliminate senescent cells, which are non-dividing proinflammatory cells that have been implicated in many age-related diseases such as lung and liver fibrosis, atherosclerosis or osteoarthritis. For this we identified uPAR as a protein broadly upregulated in senescent cells and engineered CAR T cells able to target it (senolytic CART cells). Our results showed for the first time that our senolytic CAR T cells were able to target senescent cells and be therapeutic in mouse models of chemical or NASH diet induced liver fibrosis.

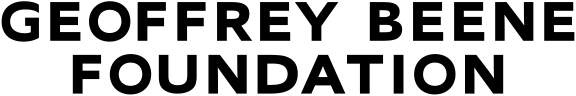

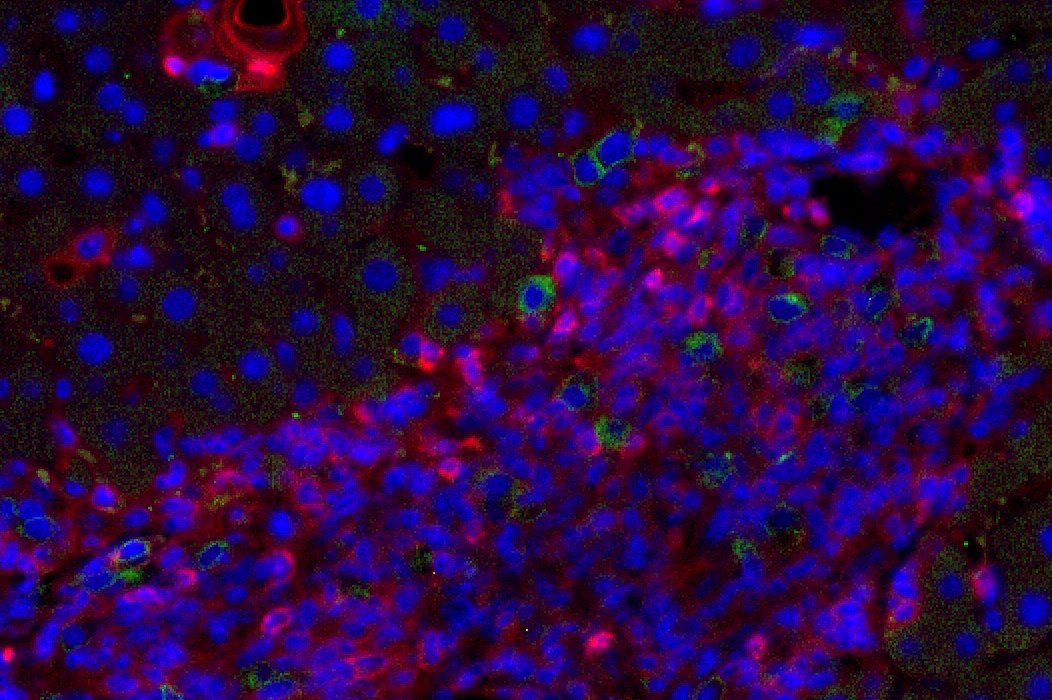

Figure 1: Liver fibrosis. NSG.2.Senescent-uPAR (red), CART (green):

CAR T cells (green) attacking senescent cells (red) in a mouse model of liver fibrosis.

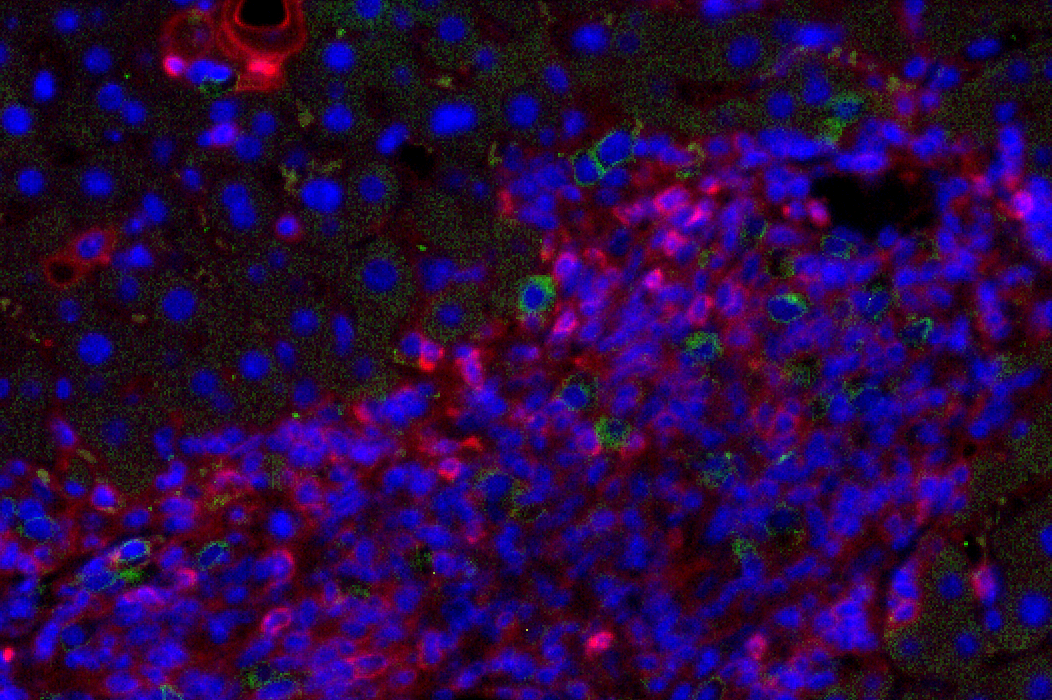

Figure 2: Liver fibrosis. NSG. Senescent-uPAR (red), CART (green):

CAR T cells (green) attacking senescent cells (red) in a mouse model of liver fibrosis.

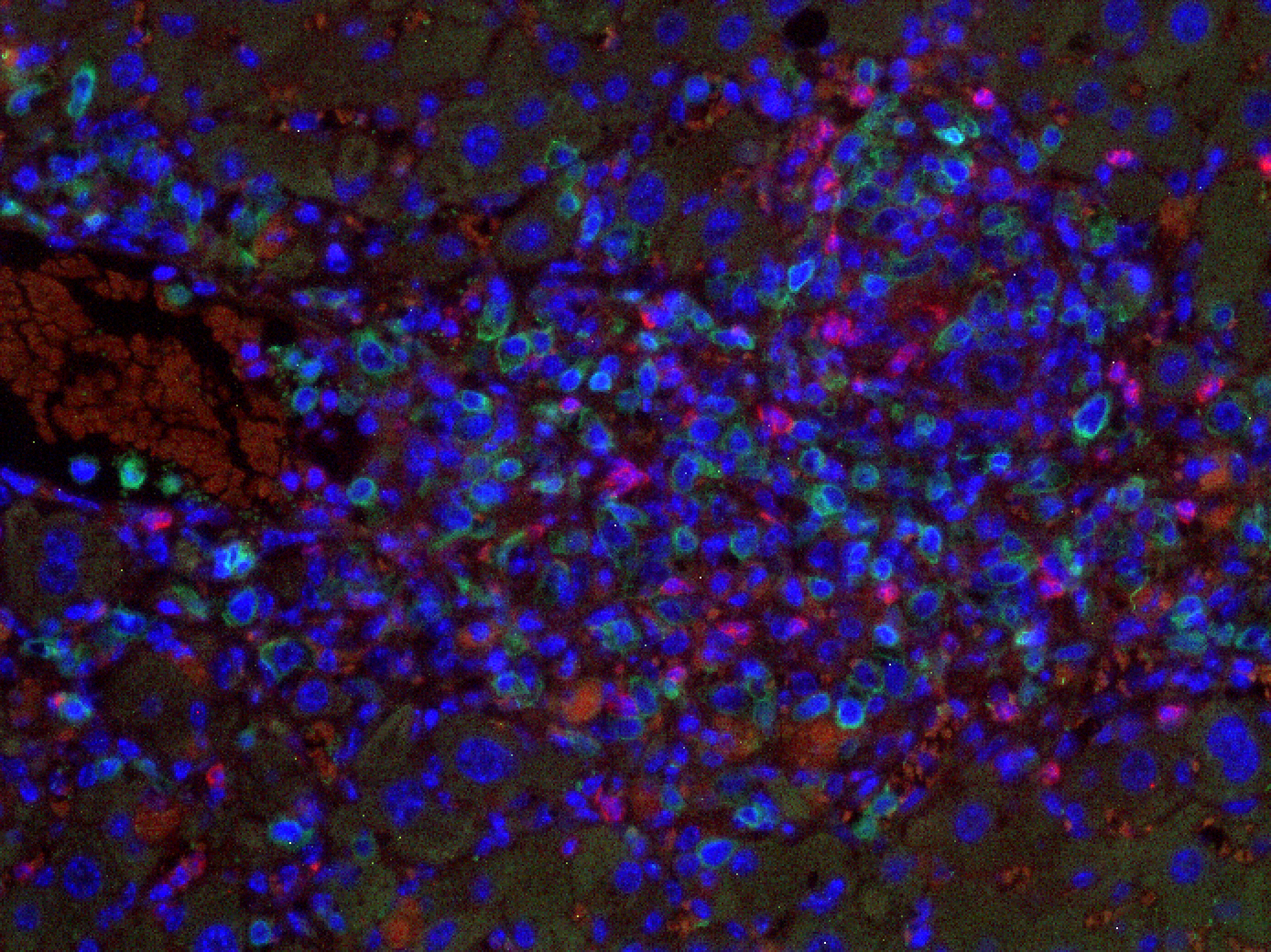

Figure 3: Liver fibrosis. IC. CART (red), SMA (green):

CAR T cells (red) attacking hepatic stellate cells (green) in a mouse model of liver fibrosis.

Figure 4: HTVI. Senescent-uPAR (red), CART (green):

CAR T cells (green) attacking senescent hepatocytes (red).

Nikolaus Schultz, PhD

Head of Knowledge Systems, Marie-Josée & Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology

Geoffrey Beene Jr. Chair

Automated retrieval of clinical data elements for the identification of genomic predictors of outcome and treatment response in cancer

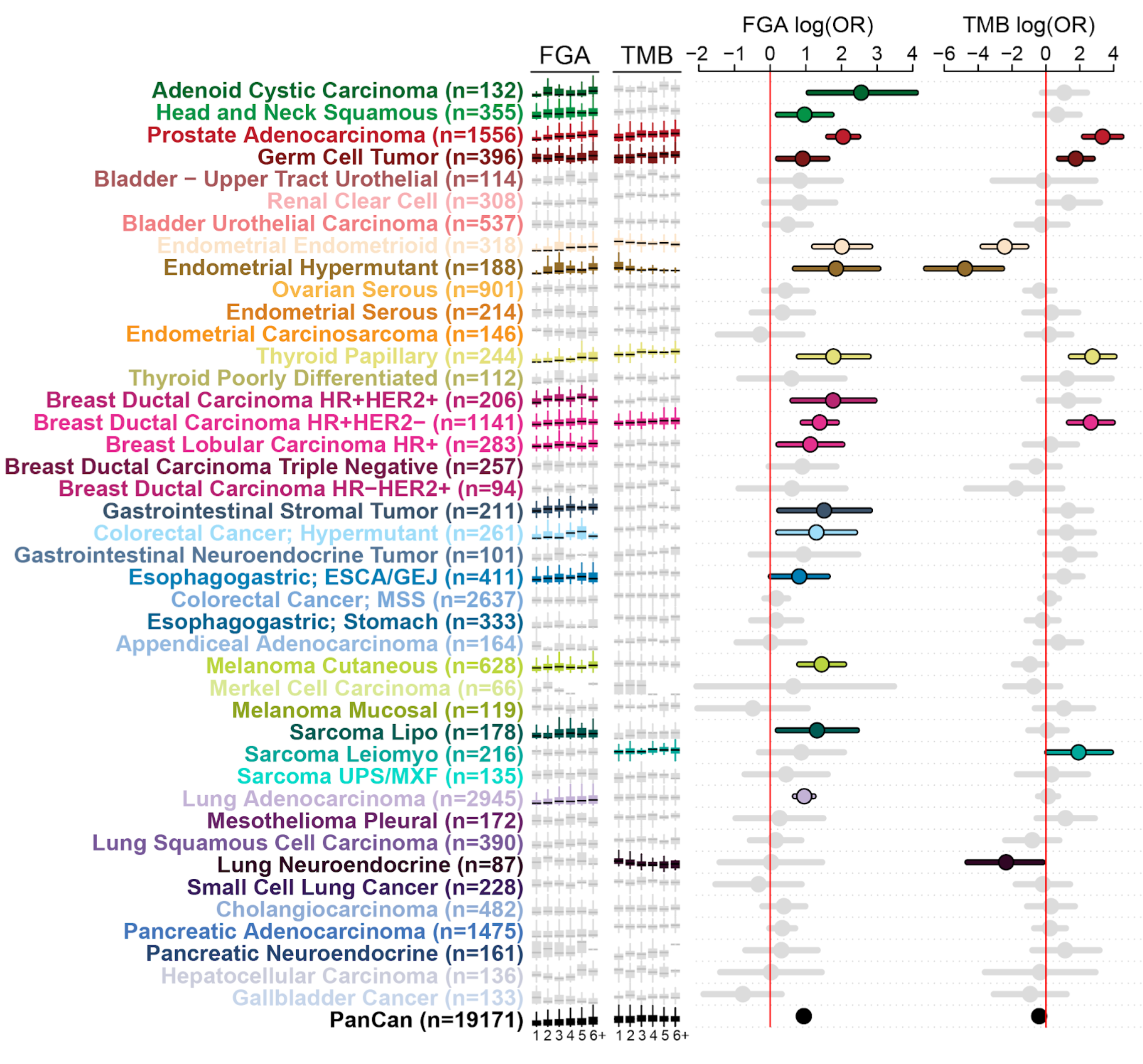

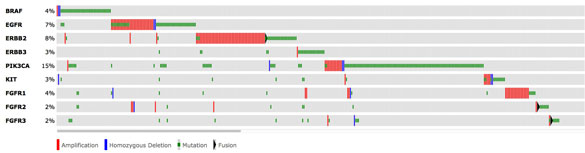

The past decade of molecular profiling of tumor samples has revealed a complex landscape of genetic variants across cancer types. As the presence of specific alterations can guide diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis, sequencing of tumor samples has now become routine as part of patient care at MSK. Using the MSK-IMPACT assay, >55,000 tumor samples have been sequenced to date. This targeted 468 gene assay has been used to discover novel alterations across many different cancer types and to reveal correlations with outcome and response to therapy. However, while the genomics data are naturally structured and easily available, retrieving and integrating clinical annotation about samples and patients presents a major challenge and bottleneck. These clinical elements include treatment information sourced from notes and order history, response ascertained from clinical notes and imaging reports, and pathologic features garnered from pathology reports, among others. Unfortunately, most of these elements remain unstructured or semi-structured at best in the electronic medical record (EMR), which precludes integration of clinical and genomic data for robust analysis. Using a variety of methods, ranging from simple pattern matching and natural language processing to state-of-the-art machine learning methods, we have begun retrieving specific clinical data elements from the electronic medical records at MSK, including treatment, response, disease progression, and metastatic events. We are now using these clinical data in conjunction with genomic alterations found in the tumor samples of these patients to identify new prognostic biomarkers and biomarkers of drug resistance. One particularly strong biomarker is the overall copy-number burden (measured as fraction genome altered, FGA) present in a sample: In some cancer types, including head and neck cancers, prostate cancer, and germ cell tumors, FGA is strongly correlated with the number of sites affected by metastases. In other cancer types, including colorectal cancer, this trend is not observed. In addition to these broader biomarkers, we are also analyzing the data set to discover predictors for metastatic spread between specific sites. For example, ERBB2-amplified breast cancers have a stronger tendency to spread to the brain. Future method improvements coupled with an ever-growing data sets should enable us to make new discoveries that can be used to guide therapy of individual patients.

Figure caption:

Genomic correlates of metastatic burden. For each cancer type, the relationship of fraction genome altered (FGA) and tumor mutation burden (TMB) is correlated with the number of metastatic sites in each patient (1 to 6+ sites from left to right in the small box plot. Significance is shown as show as the log odd’s ratio on the right.

Robert Benezra, PhD

Cancer Biology & Genetics Programs

Deputy Director for Core Technologies

Laura and Christopher Pucillo Chair in Metastasis Research

A subset of tumors of the central nervous system that are found in children and adults is driven by a genetic event in which chromosomes are rearranged in cells that initiate these tumors. This rearrangement produces a fusion protein not found in normal cells that can drive the rapid growth and expansion of cells which harbor this new protein. Chromosome rearrangements are difficult to model in mice but we have devised a protocol using a new gene editing technique (called CRISPR) that precisely models one such fusion event and recapitulates in mice the disease seen in humans. With the help of the Beene Foundation grant we are using this mouse model to understand the mechanistic basis of this tumor type and develop novel therapeutic strategies based on rational drug design.

Robert Benezra, PhD

Cancer Biology & Genetics Programs

Deputy Director for Core Technologies

Laura and Christopher Pucillo Chair in Metastasis Research

A subset of tumors of the central nervous system that are found in children and adults is driven by a genetic event in which chromosomes are rearranged in cells that initiate these tumors. This rearrangement produces a fusion protein not found in normal cells that can drive the rapid growth and expansion of cells which harbor this new protein. Chromosome rearrangements are difficult to model in mice but we have devised a protocol using a new gene editing technique (called CRISPR) that precisely models one such fusion event and recapitulates in mice the disease seen in humans. With the help of the Beene Foundation grant we are using this mouse model to understand the mechanistic basis of this tumor type and develop novel therapeutic strategies based on rational drug design.

Dinshaw J. Patel, PhD

Structural Biology Program

CRISPR-Cas Complexes

CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) – Cas (CRISPR associated genes) surveillance complexes are RNA-based adaptive immune systems employed by prokaryotes against invading nucleic acids ranging from bacteriophages to viruses. Distinct CRISPR-Cas systems can sequence-specifically target both doublestranded DNA (dsDNA) and/or single-strand RNA (ssRNA), thereby generating precise cuts, which in turn allow genetic manipulations with applications both in sensing foreign genetic elements and in medicine for disease treatment.

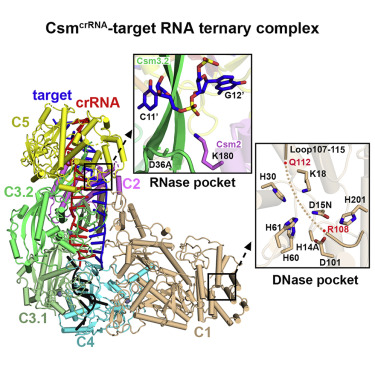

Our group has worked with Geoffrey Beene Foundation support on multi-subunit type III Csy CRISPR-Cas complexes because they u unduly exhibit multiple catalytic cleavage activities. We have applied x-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy and mutational analysis to structurally define the assembly process of Csm, crRNA and target RNA formation, as well as mechanistically characterize the respective cleavage activities and their regulation.

- The first activity of type III CRISOR-Cas systems is associated with cleavage of newly transcribed RNA target by the Csm3 subunit with a defined periodicity of cleavage sites. Our structural studies reached the following key mechanistic conclusions (Jia et Mo/. Cell 73, 264-277, 2019).

- Ruler mechanism based on 5′-repeat tag with periodic kinks crRNA-target RNA spacer du plex dictating RNA cleavage

- Pairing potential withinn 5′-repeat tag regulates autoimmunity for distinguishing host from foreign RNA

- The second activity of type Ill CRISPR-Cas systems is associated with cleavage of ssDNA at the transcriptional bubble based on the catalytic activity of the HD domain of the Csm l Our structural studies reached the following key mechanistic conclusion (Jia et al. Mo/. Ce/1 73, 264-277, 2019).

- A glutamate-rich loop spanning the DNase cleavage site adopts an autoinhibitory conformation, thereby regulating DNase

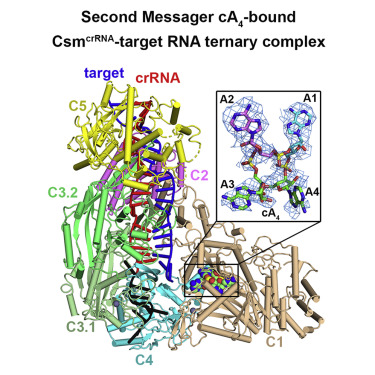

- The third activity of type III CRISPR-Cas system is associated with generation of cyclic oligoadenylate second messengers from ATP precursors in the Palm domain pocket of the Csml Our structural studies reached the following key mechanistic conclusion (Jia et al. Mo/. Cell 75, 933-943, 2019).

- Precise accommodation of ATPs in the Csml composite catalytic pocket facilitates initial conversion to linear oligoadenylates and their subsequent cyclization.

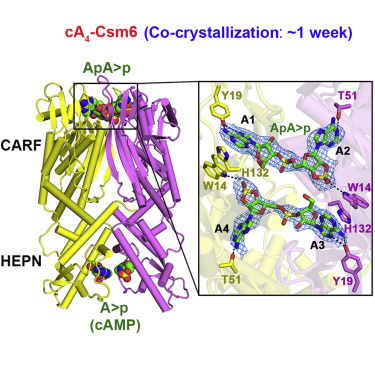

- The generated cA4 second messenger binds to the CARF domain of RNase Csm6, which in turn activates the HEPN pocket responsible for cleaving Our structural studies highlighted the following key mechanistic conclusion (Jia et al. Mo/. Ce/1 75, 944-956, 2019).

- Csm6 is a CARF domain ring nuclease that regulates HEPN domain RNase cleavage activity using a timer mechanism, thereby preventing indiscriminate ssRNA

Ning Jia, PhD, Charlie Y. Mo, PhD, Chongyuan Wang, PhD, Edward T. Eng, PhD, Luciano A. Marraffini, PhD, Dinshaw J. Patel, PhD

Type III-A CRISPR-Cas Csm Complexes: Assembly, Periodic RNA Cleavage, DNase Activity Regulation, and Autoimmunity

Highlights

- Ruler mechanism based on 5′-repeat tag dictates positioning of RNA cleavage sites

- Kinks in crRNA-target RNA duplex identify periodic RNA cleavage at 6-nt intervals

- Pairing potential with positions -2 to -5 within the 5′-repeat regulate autoimmunity

- A Glu-rich loop adopts an autoinhibitory conformation regulating DNase activity

Summary

Type ΙΙΙ CRISPR-Cas systems provide robust immunity against foreign RNA and DNA by sequence-specific RNase and target RNA-activated sequence-nonspecific DNase and RNase activities. We report on cryo-EM structures of Thermococcus onnurineus Csm crRNA binary, Csm crRNA-target RNA and Csm crRNA-target RNA anti-tag ternary complexes in the 3.1 Å range. The topological features of the crRNA 5′-repeat tag explains the 5′-ruler mechanism for defining target cleavage sites, with accessibility of positions -2 to -5 within the 5′-repeat serving as sensors for avoidance of autoimmunity. The Csm3 thumb elements introduce periodic kinks in the crRNA-target RNA duplex, facilitating cleavage of the target RNA with 6-nt periodicity. Key Glu residues within a Csm1 loop segment of Csm crRNA adopt a proposed autoinhibitory conformation suggestive of DNase activity regulation. These structural findings, complemented by mutational studies of key intermolecular contacts, provide insights into Csm crRNA complex assembly, mechanisms underlying RNA targeting and site-specific periodic cleavage, regulation of DNase cleavage activity, and autoimmunity suppression.

Graphical Abstract

Ning Jia, PhD, Roger Jones, PhD, George Sukenick, PhD, Dinshaw J. Patel, PhD

Second Messenger cA4 Formation within the Composite Csm1 Palm Pocket of Type III-A CRISPR-Cas Csm Complex and Its Release Path

Highlights

- Molecular basis underlying adenosine recognition in composite Csm1 Palm pocket

- Accommodation of linear- and cyclic-oligoadenylates in Csm1 catalytic pocket

- Mechanistic insights into ATP conversion to pppA n intermediates and cA n products

- Pathway for release of Csm1-bound cA 4 along channel between Csm1 and Csm4 subunits

Summary

Target RNA binding to crRNA-bound type III-A CRISPR-Cas multi-subunit Csm surveillance complexes activates cyclic-oligoadenylate (cA n) formation from ATP subunits positioned within the composite pair of Palm domain pockets of the Csm1 subunit. The generated cA n second messenger in turn targets the CARF domain of trans-acting RNase Csm6, triggering its HEPN domain-based RNase activity. We have undertaken cryo-EM studies on multi-subunit Thermococcus onnurineus Csm effector ternary complexes, as well as X-ray studies on Csm1–Csm4 cassette, both bound to substrate (AMPPNP), intermediates (pppA n), and products (cA n), to decipher mechanistic aspects of cA n formation and release. A network of intermolecular hydrogen bond alignments accounts for the observed adenosine specificity, with ligand positioning dictating formation of linear pppA n intermediates and subsequent cA n formation by cyclization. We combine our structural results with published functional studies to highlight mechanistic insights into the role of the Csm effector complex in mediating the cA n signaling pathway.

Graphical Abstract

Ning Jia, PhD, Roger Jones, PhD, Guangli Yang, PhD, Ouathek Ouerfelli, PhD, Dinshaw J. Patel, PhD

CRISPR-Cas III-A Csm6 CARF Domain Is a Ring Nuclease Triggering Stepwise cA4 Cleavage with ApA>p Formation Terminating RNase Activity

Highlights

- Csm6 is a CARF domain ring nuclease regulating HEPN domain RNase cleavage activity

- Two-step sequential cleavage of cA 4 by the CARF domain to ApApApA>p and ApA>p

- Csm6 CARF domain His132 plays an autoinhibitory role in controlling RNase activity

- RNA cleavage by Csm6 CARF and HEPN domains yield products with A>p 3′ ends

Summary

Type III-A CRISPR-Cas surveillance complexes containing multi-subunit Csm effector, guide, and target RNAs exhibit multiple activities, including formation of cyclic-oligoadenylates (cA n) from ATP and subsequent cA n-mediated cleavage of single-strand RNA (ssRNA) by the trans-acting Csm6 RNase. Our structure-function studies have focused on Thermococcus onnurineus Csm6 to deduce mechanistic insights into how cA 4 binding to the Csm6 CARF domain triggers the RNase activity of the Csm6 HEPN domain and what factors contribute to regulation of RNA cleavage activity. We demonstrate that the Csm6 CARF domain is a ring nuclease, whereby bound cA 4 is stepwise cleaved initially to ApApApA>p and subsequently to ApA>p in its CARF domain-binding pocket, with such cleavage bursts using a timer mechanism to regulate the RNase activity of the Csm6 HEPN domain. In addition, we establish T. onnurineus Csm6 as an adenosine-specific RNase and identify a histidine in the cA 4 CARF-binding pocket involved in autoinhibitory regulation of RNase activity.

Graphical Abstract

Scott Lowe, PhD – Provoking immune surveillance with molecularly-targeted therapies

Lung and pancreas cancers with mutations in the KRAS gene are leading causes of cancer-related death in the United States and represent a cancer subtype that currently lacks effective treatment options. Mutant KRAS causes tumorigenesis by activating cell signaling programs that promote uncontrolled proliferation, in part, through a molecular signaling mechanism known as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Developing strategies to treat KRAS mutant tumors has been a goal of Scott Lowe, the chairman of the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center, and other MSKCC investigators. In work partially supported by the Beene Center, the Lowe laboratory discovered that the combination of FDA approved drugs trametinib (which inhibits the MAPK pathway) and palbociclib (which blocks an enzyme needed for cell division) causes KRAS mutant cancer cells to halt proliferation, while also provoking an immune response that causes the immune cells to see and kill the cancer cells, leading to tumor shrinkage.

The basis for tumor shrinkage involves the ability of the drugs together (but not on their own) to induce a cellular program known as “senescence”, which potently suppresses the ability of cells to divide. Additionally, senescent cells release factors that attrack immune cells and increase the levels of immune cell binding proteins on their surface. The net result of these processes leads to an immune response against the cancer, in this case mediated by an immune cell type known “natural killer cells” (for the detailed report, see Ruscetti, Leibold, Bott, et al., Science 362:1416).

While the goal of most cancer-fighting drugs is to kill tumor cells, these studies demonstrate that drugs that do not directly kill tumor cells but halt proliferation via senescence can cause the regression of tumors by reawakening the immune system to recognize and kill cancer cells. As no effective drugs for KRAS-driven cancers have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, these new results raise the hope that effective therapies might yet be possible by strategies that target cancer cells and simultaneously enlist the immune system. The team is now looking to combine these drugs with the immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors. They hope that this pairing will further enhance the immune system’s attack on tumors.

Figure. Natural killer cells (red) attach to and kill senescent lung tumor cells (green) following combination drug treatment.

Project title: Mitotic Stress Response (MSR) and Cancer

PI: Meng-Fu Bryan Tsou, PhD

Associate Member

Cell Biology Program

To increase cell number, cancer cells first go through the growth phase known as “interphase”, followed by the division phase called “mitosis”. Cycling cells in interphase are subjected to quality controls in preparation for efficient mitosis. However, when unfit or overstressed cells escape the radar and undergo cell division, they often get trapped in a disturbed, lengthy mitosis, followed by activation of cell death or cell cycle arrest in processes collectively called the mitotic stress response (MSR). MSR is thus a critical gatekeeper safeguarding at the end of cell cycle to remove overstressed or unfit cells from the population. In addition, based on MSR, the idea of using antimitotic drugs (antimitotics) to suppress cancer growth has become very attractive, and a number of chemicals, including Paclitaxel, have been developed for cancer chemotherapy.

Ironically, however, the molecular mechanism underlying MSR is largely unclear (not until our recent breakthrough). Neither the machinery sensing nor measuring the mitotic stress, nor the downstream response leading to cell death is understood. These “missing gaps” in the MSR pathway have not only impaired our capability (and creativity) to effectively use the antimitotics for cancer treatment, but also limited our understanding of how dividing/mitotic cells respond to cellular stress in general, both of which are fundamentally important to human physiology and diseases.

Supported by the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center, we have developed a novel cell-based assay in which whole-genome, gene-targeting-based screens can be conducted to systematically dissected the MSR program. We have identified a number of novel players acting either upstream or downstream of the tumor suppressor protein p53 in the MSR pathway. In particular, 53BP1 and USP28 are two proteins working together to transduce a wide range of mitotic stress into p53 activation and cell death, thereby removing unfit cells with disturbed mitosis. Our findings shed lights on how cancer cells die or live in response to antimitotic drugs, enabling rational development of new ideas that can effectively complement or synergize with the current antimitotics treatment.

Key Points:

- MSR function at the end of cell cycle to remove unfit cells with disturbed mitosis.

- Antimitotic drugs are developed to treat cancer based on MSR, albeit with moderate levels of clinical success.

- The molecular mechanism underlying MSR is ironically unclear.

- We have identified 53BP1-USP28-p53-p21 as a linear pathway mediating MSR, allowing more effective designs to complement or synergize with the current antimitotics treatment.

Jason S. Lewis, PhD – Positron emission tomography (PET) is uniquely suited for the noninvasive imaging and repetitive quantification of biological processes in cancer. The GBCRC grant in 2009 allowed us, for the first time at MSK, to initiate a program to develop a novel imaging agents for the quantitative PET imaging of breast tumors for improved early detection, staging, monitoring of Herceptin therapy. The GBCRC grant supported the optimized production of Zirconium-89 (Zr-89, a radioisotope used in PET), and the successful translation of Zr-89-Herceptin into the clinic. It is important to note that the support from the GBCRC has had wider and broader implications that were not originally conceived. The use of Zr-89 from this original study has now lead to five first-in-human imaging trials at MSK with Zr-89 labeled antibodies targeting a broad range of indications including gastric, prostate, pancreas and brain cancer. It has generated significant levels of NIH funding (> $5 million USD), additional philanthropic support and industrial sponsorship of basic research projects and clinical trials. Importantly, the success of this work has led to publications in the highest level of scientific journal and has been the foundation of young scientists trained at MSK starting their own independent cancer-based programs at institutions such as UCSF, the Karmanos Cancer Center and CUNY-Hunter.

Dinshaw Patel, PhD, MSKCC Structural Biology Program

Jan 6, 2019

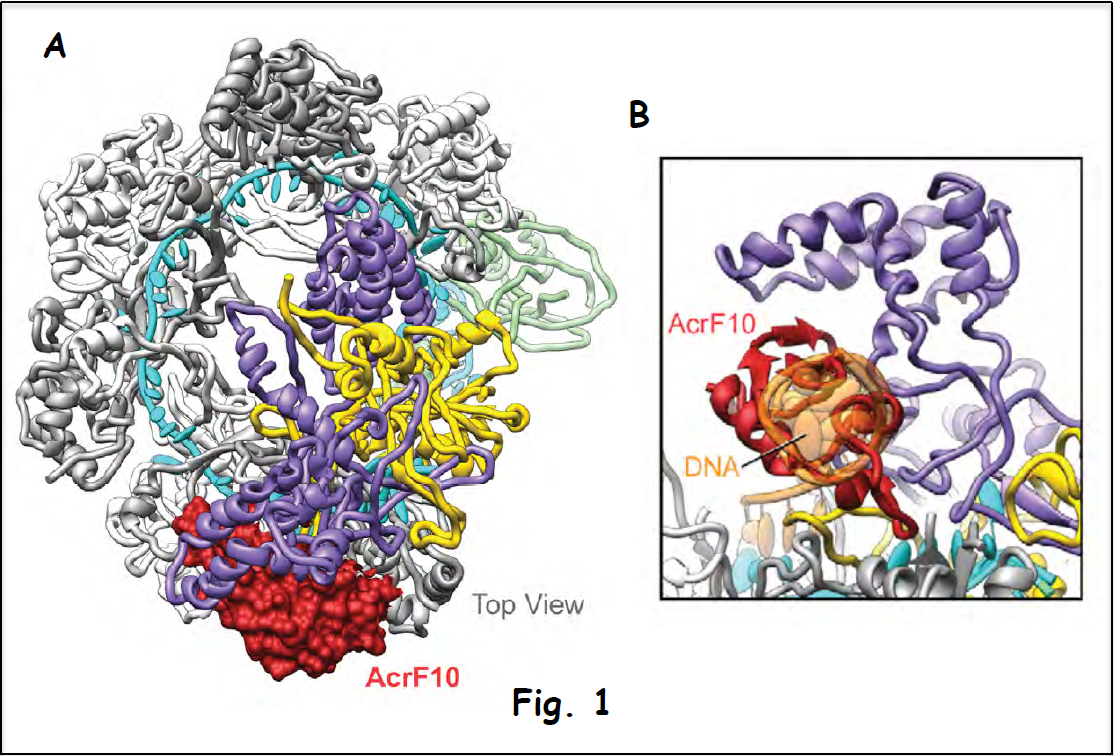

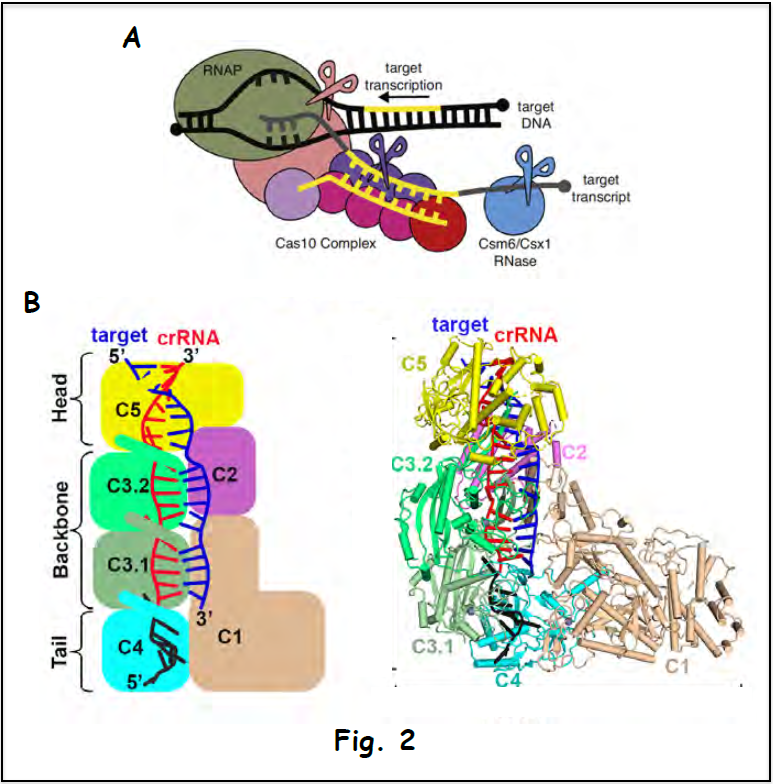

Prokaryotic cells possess CRISPR-Cas mediated adaptive immune systems that protect them from foreign genetic elements such as invading bacteriophages and viruses. A fundamental understanding of the mechanistic principles underlying CRISPR-Cas-mediated surveillance and cleavage of invading RNA and DNA has had profound implications on applications of this methodology to gene editing technologies in biology and medicine.

The Patel structural biology laboratory at MSKCC supported by the Beene Foundation has focused its efforts on multi-subunit Cas effector scaffolds, their complexes with guide RNA and added target DNA/RNA, as well as virus-evolved anti-CRISPR proteins that shut down the surveillance pathway.

Figure 1A shows the cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the complex between the Csy surveillance complex (multi-subunit Csy bound to guide RNA) targeted by the anti-CRISPR protein AcrF10 (in red). This structure demonstrates that the anti-CRISPR protein suppresses the surveillance pathway by occluding recognition of the signature (PAM element) unique to viral DNA (expansion in Fig. 1B), thus preventing degradation of the invader’s genetic information (Guo et al. 2017).

The multi-subunit Csm surveillance complex provides robust immunity against foreign RNA and DNA by sequence specific RNase and target RNA-activated DNase and RNase activities (shown schematically in Fig. 2A). Structure-function studies have addressed the assembly of the complex (cryo-EM structure of the Csm complex with bound guide RNA in red and target RNA in blue is shown in Fig. 2B), which provides the platform for a mechanistic understanding of periodic RNA cleavage, how the DNase activity is regulated and the autoimmunity principles that discriminate between host and invading DNA (Jia et al. 2019).

Ongoing efforts are addressing the principles underlying generation of cyclic-oligoadenylate from ATP (the fundamental energy source) within a pocket on the Csm surveillance complex and how such second messengers activate nuclease activity associated within a trans-acting RNase Csm6 and how this activity is regulated (manuscript in preparation).

Publications (support from the Beene Foundation listed in the Acknowledgment)

Guo, T. W., Bartesaghi, A., Yang, H., Falconieri, V., Rao, P., Merk, A., Eng, E. T., Raczkowski,

- M., Fox, T., Earl, L. A., Patel, D. J. & Subramaniam, S. (2017). Cryo-EM structures reveal mechanism and inhibition of DNA targeting by a CRISPR-Cas surveillance complex. Cell 171, 414-426.

Jia, N., Wang, C., Mo, C. Y., Eng, E. T., Marraffini, L. A. & Patel, D. J. (2019). Type III-A CRISPR Csm complexes: Assembly, target RNA recognition, periodic cleavage and autoimmunity.

‘

‘

Andrea Ventura, MD, PhD– A novel approach for the identification of microRNA targets in vivo

Thanks to funding from the Beene Foundation, my laboratory has been able to pursue a novel and very fruitful research path. We have pioneered the use of in vivo somatic genome editing to accurately model chromosomal rearrangements in vivo, and we have used this novel strategy to: a) develop preclinical models of lung and brain cancer; b) identify new oncogenic drivers; and c) test novel therapeutic strategies.”

Key Points:

- We were the first to demonstrate that CRISPR-Cas9 based genome editing can be adapted to model chromosomal rearrangements directly in vivo

- We have generated a novel mouse model of EML4-ALK-driven lung cancer and shown that it recapitulate the biological and molecular characteristics of the human counterpart

- We have identified BCAN-NTRK1 as a novel driver of brain cancer, generated a mouse model of this highly lethal tumor, and shown that the presence of this rearrangement confers sensitivity to Entrectinib, an experimental inhibitor of NTRK.

- We have developed a novel algorithm to identify highly specific guideRNA.

“Funding from the Beene Foundation has allowed us to develop a novel and powerful strategy to identify miRNA targets in vivo, thus addressing a major problem in the miRNA field. As an essential component of this novel strategy we have generated a genetically engineered mouse strain that greatly simplifies the task of identifying miRNA-mRNA interactions in cells and in tissues. We are currently using this model to explore the role of miRNAs during tumor progression.”

Ross Levine, MD– Role of the Cohesin Complex in Leukemic Transformation

Cancer is a disease of disordered genes—either through gene mutations or abnormal gene expression. Normal gene expression is controlled through regulatory elements, such as transcription factors, as well as DNA architectural structure. Recently, loss of function mutations within genes of the cohesin complex were identified in multiple malignancies including bladder cancer (20-35%), Ewing sarcoma (40-60%), and acute myeloid leukemia (12-20%). The cohesin complex, a multi-protein ring, is canonically known to align and stabilize replicated chromosomes prior to cell division. Although initially thought to lead to unequal chromosomal separation in dividing cells, our preliminary data shows this has not been observed, either in large patient cohorts or mouse models. We identified a potential alternate mechanism whereby drivers of cell-type specific gene expression and hematopoietic development are impaired through alteration in 3-dimensional nuclear organization and gene structure. We suspect this result is due to impaired cohesin-mediated DNA looping at genes controlled by regulatory elements known as enhancers. These tissue-specific enhancers are physically looped to the gene promoter with the aid of the cohesin complex, resulting in recruitment of high efficiency transcriptional machinery. While complete loss of the obligate cohesin ring member, Smc3, was lethal, we found that deletion of the adapter and localization proteins, Stag2 and Stag1 are survivable events. Stag2 is the most commonly mutated cohesin gene in both acute myeloid leukemia and solid tumors, and similar to the Smc3 single gene deletion, Stag2 knockout results in impaired differentiation and in increased Stag1 expression, likely as a redundancy mechanism. Combined deletion of Stag2 and Stag1 led to a lethal phenotype similar to Smc3 knockout and thus we identify Stag1 as well as the Smc3 deacetylase, Hdac8 as unique tumor-specific liability in cohesin mutant cancers. Our work aims to use our mouse models, large cohort of banked cohesin-mutant patient samples, and basic molecular techniques to understand the molecular mechanism of cohesin mutant cancer and identify novel targeted therapies in this pathway.

Stag2 deficient hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells have fragmented and supernumerary nucleoli, similar to patients with Cornelia deLange syndrome and Smc3 heterozygous bone marrow

Jayanta Chaudhuri, PhD– Nucleosome remodeling in DNA damage response

Breaks DNA constitute one of the most toxic lesions that can occur in a cell. If left unrepaired, they can cause either cell death or tumorigenesis. Despite this toxicity, development of a fully functional our immune system relies on a series of programmed DNA breakage events. Thus, a failure to generate these breaks lead to immunodeficiency syndromes while aberrations in the DNA repair phase result in lymphomas. Indeed many kinds of B cell lymphomas arise due to defects in the programmed DNA break-repair events that occur in B cells. A major focus of our laboratory is to understand the molecular pathways that make the breaks and then mediate DNA repair to promote immunity while suppressing genomic instability and lymphomagenesis. Through funding from the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Center, we have been able to discover a protein called BRIT1 as being a new player in DNA repair in B cells. The Beene Award also helped us establish a productive collaboration with the Jasin lab in the MSKCC Developmental Biology Program to design novel strategies to assess DNA repair capacity in B cells. Currently, we are generating novel mouse models to elucidate how packaging of the DNA into structures called nucleosomes allow programmed DNA break-repair in lymphocytes.

The major discoveries we have made in the past year through funding from the Beene Cancer Center are as follows:

- The protein BRIT1 is expressed in B cells

- Loss of BRIT1 in mice leads to impaired B cell function in immunity

- Loss of BRIT1 also leads to unrepaired DNA breaks in lymphocytes

- A robust assay has been established to assess DNA repair in B cells

The work has been published in two papers from our lab.

- Yen WF, Chaudhry A, Vaidyanathan B, Yewdell WT, Pucella JN, Sharma R, Liang Y, Li K, Rudensky AY and Chaudhuri J. BRCT-domain protein BRIT1 influences class switch recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017; 114(31): 8354-8359.

- Chen CC, Kass EM, Yen WF, Ludwig T, Moynahan ME, Chaudhuri J and Jasin M. ATM loss leads to synthetic lethality in BRCA1 BRCT mutant mice associated with exacerbated defects in homology-directed repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017; 114(29): 7665-7670.

Maurizio Scaltriti, PhD

Mechanisms of resistance to PI3K-alpha inhibitors in breast cancer

Maurizio Scaltriti

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer worldwide and, although treatments have improved greatly over the last decade, it remains the leading cause of cancer-related death in women. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway, often hyperactivated in this malignancy as a result of a mutation in a gene called PIK3CA, is essential for cell growth, proliferation, survival and tumor progression.

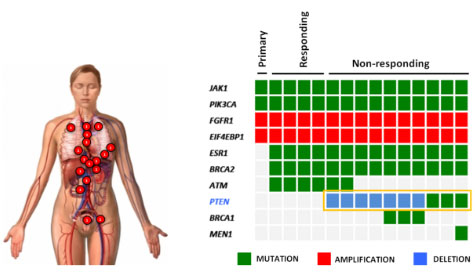

Based on the important role of the PI3K pathway in breast cancer and other tumors, a number of PI3K inhibitors are in clinical development as anti-cancer agents. A new generation of PI3K inhibitors with selective and potent inhibitory action against PIK3CA has shown unprecedented clinical activity. However, not all patients bearing PIK3CA-mutated tumors benefit from these agents, and those patients with advanced disease who initially respond inevitably become resistant to these agents. The identification of the mechanisms that breast cancer cells adopt to escape therapy will allow better identification (and selection) of patients that are more likely to respond and, concomitantly, shed light on novel possible therapeutic strategies that may prevent or overcome resistance.

In this work Dr. Scaltriti found two of such mechanisms. One can occur as a consequence of prolonged exposure of tumor cells to the treatment, and one is likely the outcome of pre-existing conditions of the tumors that resulted in intrinsic refractoriness to pharmacological PI3K inhibition.

The first discovery came from an observation made on a single metastatic breast cancer patient that, after an initial and durable response to one of these specific PI3K inhibitors, became resistant to the therapy. After disease progression, she decided to donate her body for scientific purposes and, at the time of death, Dr. Scaltriti harvested 14 different metastases during an autopsy. Strikingly, in all the metastases that became resistant to therapy we found that another gene called PTEN, the natural break of the PI3K pathway, was disrupted and non-functional (Figure on the left). This correlation was then validated in the laboratory, where he confirmed that the loss of PTEN function is sufficient to limit the sensitivity of tumor cells to these specific PI3K inhibitors. These results were published in the prestigious journal Nature in early 2015 and reproduced by other investigators in the field.

In addition to this mechanism of drug resistance emerging upon prolonged treatment, Dr. Scaltriti discovered that some tumors, apparently identical to the ones responding to the therapy, are intrinsically refractory to PI3K inhibition. He found that these tumors can bypass the inhibitory effects of PI3K inhibition by quickly switching on another parallel pathway that, ultimately, compensates for the lack of PI3K signaling. This was proven to be essential because the concomitant suppression of PI3K and this compensatory mechanism resulted in dramatic antitumor activity. These findings were published in Cancer Cell in July 2016 and this novel therapeutic combination is now being patented by Memorial Sloan Kettering.

Ross Levine

Role of the Cohesin Complex in Leukemic Transformation

G. Beene Award Recipient 2015

Dr. Levine’s studies have focused on newly identified mutations in a class of genes called the cohesin complex. Genome sequencing has identified mutations in these cohesin genes in leukemias and in brain tumors, sarcomas, and bladder cancers, and we have used support from the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center to shed new light into how cohesin mutations contribute to cancer development and to identify new therapeutic targets in cohesin-mutant cancers. This includes the development of the first animal models of cohesin mutant leukemias and identification of new therapeutic targets which will enter the clinic in near-term precision clinical trials.

– We have developed the first animal models of cohesin mutant cancers

– We have used these models to uncover novel insights into how cohesin mutations alter gene expression and contribute to transformation by altering epigenetic regulation

– We have identified novel therapeutic targets specific to cohesin mutant cancers which we are testing in preclinical studies with an aim to transition these to the clinic in the near future

Nucleolar staining of bone marrow stem and progenitor cells from mice with haploinsufficiency of Smc3 reveal supernumerary and fragmented nucleoli similar to patients with Roberts Syndrome, where Smc3 is functionally impaired. Image by Aaron Viny, Levine Lab, Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program

Lay abstract summary of “Genomic and neoantigen landscape underlying response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with NSCLCs”, supported by The Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center.

Principal Investigator: Matthew Hellmann, MD; Assistant Attending; Department of Medicine

There has been a recent breakthrough in the treatment of patients with lung cancers: medicines that can effectively stimulate the patient’s immune system to attack his or her cancer. These medicines are called “immunotherapies” and MSKCC has been a prominent leader in the clinical development of these therapies. The immune system is the body’s protection against foreign intruders, such as viruses or bacteria, and it can also recognize cancers. The immune system is normally controlled by well-coordinated “on” and “off” signals (called “checkpoints”) that tell the immune system to attack when appropriate (e.g. during an infection), but also recede to the background when not needed. In the setting of cancers, the immune system can use the “on” signals to fight and may even eliminate some cancers before they ever are recognized. But cancers can also hijack these signals, to stifle immune attack and allow cancers to grow. New immunotherapies work by modulating these signals, to counteract the immune suppressive effects of cancers, in order to restore and reinvigorate the immune system’s attack against cancers. MSKCC has led the way in bringing these medicines out of the laboratory and into the clinic in order to help patients with cancers. This approach has produced incredible results in some patients with a variety of types of cancers, including lung cancers, but other patients do not respond at all. This experience raised a critically important clinical question: Why do some patients respond while others do not? In order to optimize and better personalize the use of these therapies, the goal of this study is to see if the genetic makeup lung cancer genes predicts response to immunotherapy.

How can the genes of lung cancers be used to understand response to immunotherapy? As a cancer develops, important changes occur in cancer genes (called mutations) that allow it to grow and act differently from normal cells. As a result, the genes of cancers are very different from the genes of the normal body. Since these genetic changes are found only in cancers and are different from the normal body, Dr. Hellmann and colleagues believe these mutations are a crucial component of how the immune system recognizes a cancer as “foreign,” and worthy of attack just like a viral infection. In particular, they hypothesize that the more genetic changes found in a cancer means it will appear more foreign to the immune system and it will be more likely to respond to immunotherapies. “Next Generation Sequencing” technology now allows them to read the entire genetic code of a cancer and compare it to the normal genetic code to find what changes that are present only in cancer genes. With support from the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center, the laboratory has used this technology to study the cancer genes of patients with lung cancers treated with immunotherapies, some of whom have benefited greatly and others not at all.

Dr. Hellman and his colleagues have performed sequencing of 34 patients with lung cancers treated with an immunotherapy called pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1) and recently published their results in the prestigious journal Science. They found that those patients with elevated burden of cancer mutations (“somatic mutation burden”) were indeed more likely to have durable response to treatment. Importantly, they also identified a neoantigen-specific immune response in an excellent responder to pembrolizumab, demonstrating (for the first time) the proof of principle that responses to immunotherapies in patients with lung cancers may be related to the immune system’s capacity to recognize cancer-associated mutations. Overall, this work has demonstrated a substantial impact of the genetic landscape and the potential role of neoantigens in mediating response to immunotherapies and will help improve the use of these agents clinically.

President, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Craig B. Thompson, MD

Regarding the American diet, Dr. Thompson explains “… one of the fundamental things about the Geoffrey Beene Foundation is to shine a light on that issue. So the question is what are those unhealthy foods? For a long time we thought that the foods were the fats that we eat. It turns out for cancer not to be the big culprit. It turns out to be the sugars, the simple sugars that we eat that are the most dangerous and that came from basic research that was funded here by the Geoffrey Beene Foundation at Memorial Sloan Kettering.”

Yu Chen, MD, PhD – “The Newest Precision Medicine Tool: Prostate Cancer Organoids”

The prostate cancer within each afflicted patient is a unique disease that harbors distinct genetic mutations. These variations in gene mutations between cancers underlie the vast differences in tumor behavior among cancer patients affecting tumor growth rate, their propensity to spread, and their responsiveness to different cancer treatments. Even within each individual patient, there are different “subclones” of cancer cells with different mutations such that they may respond differently to therapy eventually producing disease progression and drug resistance. With the rapid development of new prostate cancer therapies, the major need for personalized cancer treatment is to understand how different mutations between patients (termed “intertumoral heterogeneity”) and within a patient (termed “intratumoral heterogeneity”) can predict for cancer behavior and response to treatment.

Researchers often study cancer cell behavior in cell culture where cells derived from a patient’s tumor are established in Petri dishes and can be grown in the laboratory. Indeed, such cells are frequently used to understand how the gene mutations in cancer cells influence cancer cell behavior and to evaluate the action of new cancer drugs. Unfortunately, prostate cancers have been extremely difficult to grow in the laboratory. With support from a Geoffrey Been Cancer Research Center grant, Dr. Yu Chen’s laboratory optimized conditions to grow prostate cancer cells directly from patient biopsies. Rather than cultures on the bottom of a Petri dish, these cells are grown in 3-dimentions, which Dr. Chen has shown better recapitulates the diverse behavior seen in patients’ tumors. These lines can then be grafted into mice, where they produce tumors that mirror those in patients and can be used to evaluate new drugs (see Fig).

Over the past two years, the Chen laboratory has established ~15 such “organoid” lines from patients that have undergone biopsies at MSKCC. Each line harbors a different set of mutations and together, they encompass a large repertoire of the genetic configurations found in different prostate cancer patients. They are now using these lines to understand how mutations affect the clinical presentation and therapeutic sensitivity to different drugs or drug combinations. Such new models should greatly accelerate the pace with which new treatments can be delivered to prostate cancer patients

Omar Abdel-Wahab, MD

Assistant Member, Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program and Leukemia Service Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Therapeutic Advances in Rare Forms of Blood Cancer Driven by BRAF Mutations.

The BRAF gene encodes a “molecular switch” that normally transmits growth-promoting signals from outside of the cell to the nucleus to stimulate cell division. Certain cancers acquire mutations in the BRAF gene, leading to the production of a protein that is always switched on and, consequently, promotes inappropriate cell division. Although such BRAF mutations are quite common in solid tumors such as melanoma and colon cancer, they are almost never seen in blood cancers except for in two poorly understood diseases known as hairy cell leukemia and systemic histiocytoses.

In 2012 and 2013 Dr. Abdel Wahab and colleagues received 2 separate grants from the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center at MSKCC to BRAF mutations in hairy cell leukemia and systemic histiocytoses. Dr. Abdel Wahab’s team was particularly interested in these diseases because the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib (Zelboraf) had proven very effective for patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma and was FDA-approved for this condition already. They therefore carried out 2 separate clinical trials for each condition, both of which were recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine (see publication lists below). In both studies, they found that patients with hairy cell leukemia or histiocytosis who had disease refractory to conventional chemotherapy responded exceptionally well to vemurafenib (please see Figure 1 below for some examples). These results are now being used to obtain FDA-approval for vemurafenib in both disorders.

While doing this work, Dr. Abdel Wahab’s team realized that while 100% of patients with hairy cell leukemia have the BRAF mutation, only ~50% of histiocytosis patients have the BRAF mutation. This then led to the discovery that the other half of histiocytosis patients have mutations in other members of the BRAF signaling pathway and respond to other types of specialized therapies against the mutant proteins. They are now initiating a clinical trial of one these new drugs (called cobimetinib (or Cotellic)) for histiocytosis patients that lack the BRAF mutation. The results of this treatment in the first few patients have been extremely encouraging (please see Figure 2 below). Consequently, funding from the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center will directly impact the lives of patients with these diseases.

Publications:

(1) Tiacci E (co-first), Park JH (co-first), De Carolis L, Chung SS, Broccoli A, Scott S, Zaja F, Devlin S, Pulsoni A, Chung YR, Cimminiello M, Kim E, Rossi D, Stone RM, Motta G, Saven A, Varettoni M, Altman JK, Anastasia A, Grever MR, Ambrosetti A, Rai KR, Fraticelli V, Lacouture ME, Carella AM, Levine RL, Leoni P, Rambaldi A, Falzetti F, Ascani S, Capponi M, Martelli MP, Park CY, Pileri SA, Rosen N, Foà R, Berger MF, Zinzani PL, Abdel-Wahab O (equal contributors), Falini B (equal contributors), Tallman MS (equal contributors). Targeting Mutant BRAF in Relapsed or Refractory Hairy-Cell Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 29;373(18):1733-47.

(2) Hyman DM, Puzanov I, Subbiah V, Faris JE, Chau I, Blay JY, Wolf J, Raje NS, Diamond EL, Hollebecque A, Gervais R, Elez-Fernandez ME, Italiano A, Hofheinz RD, Hidalgo M, Chan E, Schuler M, Lasserre SF, Makrutzki M, Sirzen F, Veronese ML, Tabernero J, Baselga J. Vemurafenib in Multiple Nonmelanoma Cancers with BRAF V600 Mutations. N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 20;373(8):726-36.

(3) Diamond EL, Durham BH, Haroche J, Yao Z, Ma J, Parikh SA, Wang Z, Choi J, Kim E, Cohen- Aubart F, Lee SC, Gao Y, Micol JB, Campbell P, Walsh MP, Sylvester B, Dolgalev I, Aminova O, Heguy A, Zappile P, Nakitandwe J, Ganzel C, Dalton JD, Ellison DW, Estrada-Veras J, Lacouture M, Gahl WA, Stephens PJ, Miller VA, Ross JS, Ali SM, Briggs SR, Fasan O, Block J, Heritier S, Donadieu J, Solit DB, Hyman DM, Baselga J, Janku F, Taylor BS, Park CY, Amoura Z, Dogan A, Emile JF, Rosen N, Gruber TA, Abdel-Wahab

O. Diverse and Targetable Kinase Alterations Drive Histiocytic Neoplasms. Cancer Discov. 2015 Nov 13. Epub ahead of print]

Figure 1. Clinical responses of BRAF-mutant (A) hairy cell leukemia and (B, C) systemic histiocytoses to the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib. The Geoffrey Beene Cancer Center at MSKCC helped to fund work related to the clinical trials involving the patients shown here. (A) Shows the percentage of blood cells which contain leukemia cells before drug treatment and at specific intervals after drug treatment. (B) Shows the skin of a patient affected by histiocytosis before and after treatment. (C) Shows an MRI scan of the brain of a histiocytosis patient before and after treatment. The green arrow points to the parts of the brain that were infiltrated by the disease.

Figure 2. Clinical response of MEK1-mutant systemic histiocytosis to the MEK inhibitor cobimetinib. Through an effort funded by the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Center we identified that ~25% of histiocytosis patients harbor a mutation in the protein just downstream of BRAF, called MEK1. Dr. Abdel Wahab since found that these patients are very sensitive to the MEK inhibitor cobimetinib and have initiated a second clinical trial of this drug for these patients. Shown is a PET scan of a MEK1-mutant histiocytosis patient before and after cobimetinib treatment where disease infiltrated the heart, kidneys, and facial sinues—all of which improved with drug treatment.

Michael Berger, PhD–“Having an IMPACT on treatment decisions”

The concept of precision cancer medicine is based on the premise that each patient’s cancer is unique and should be treated based on the molecular changes occurring in their tumor. A growing number of cancer drugs specifically target cancers with particularly genetic events and thus are being administered according to the presence or absence of key tumor genetic alterations that predict the likelihood of the therapy’s success.

Accordingly, high-throughput mutation profiling of the DNA from every cancer for the mutational status of every known cancer gene is central for the success of precision cancer medicine.

With the support of the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center, a test called MSK-IMPACT, which is capable of detecting all possible mutations involving 341 genes with the greatest clinical and/or biological significance for cancer, was developed. Through extensive experimentation, Dr. Berger and colleagues optimized the performance of the test for “challenging” types of clinical specimens. Following initial success in pilot studies, Dr. Berger has since deployed production-scale MSK-IMPACT testing retrospectively for translational research and prospectively for clinical diagnosis of patients.

In the last 2 years, Dr. Berger and his colleagues have published more than 20 research articles describing studies with MSK-IMPACT to identify clinically relevant mutations. Most significantly, the MSK-IMPACT platform has been successfully implemented in the clinical molecular diagnostics laboratory of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center to directly inform treatment decisions. Based largely on the success of the work funded by the Geoffrey Beene grant, Dr. Berger assumed oversight of the development of validation of MSK-IMPACT as a clinical test. Dr. Berger obtained full approval from the New York State Department of Health allowing him to report results back to patients and their doctors. This promises to improve treatment decisions for numerous patients and to pre-identify patients eligible for current and future clinical trials.

KeyPoints:

- MSK-IMPACT was developed to detect all possible mutations involving 341 genes

- MSK-IMPACT enables informed treatment decisions and can pre-identify patients for eligible for clinical trials to test new drugs or drug combinations

- Over 20 research articles have been published where MSK-IMPACT has been used

- MSK-IMPACT has been implemented into the molecular diagnostics lab to directly inform treatment decisions

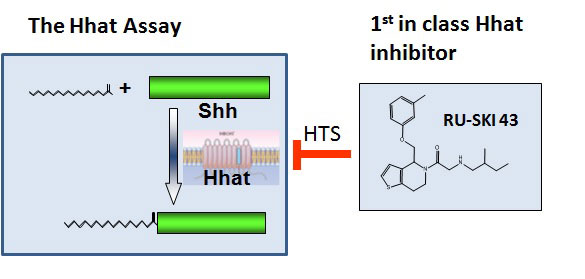

Marilyn Resh, PhD – Tackling lethal pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer is an extremely lethal cancer for which no effective therapies are currently available. The laboratory of Marilyn Resh is focused on a molecular pathway which is controlled by the Sonic hedgehog (Shh) protein and contributes to pancreatic cancer development. Shh is produced by embryos as they develop. After birth, Shh expression is turned off, and most normal adult tissues do not make Shh. However, in pancreatic cancer, Shh is aberrantly turned back “on”. This abnormal expression of Shh helps to promote the growth of pancreatic cancer. In order to function normally, Shh must be modified by attachment of a fatty acid, palmitate. This process is known as palmitoylation, and is mediated by a protein termed Hhat (Hedgehog palmitoyl acyltransferase). Dr. Resh and her colleagues hypothesized that it would be possible to block the action of Shh by inhibiting the ability of Hhat to attach palmitate to Shh.

Using funds from the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center, Dr. Resh set up a strategy to test her hypothesis and in doing so develop potential new strategies to treat pancreatic cancer. In order to identify Hhat inhibitors, she developed a method to measure Shh palmitoylation and used it to screen a “library” of 85,000 chemical compounds. This screen identified 95 compounds that directly inhibit Hhat, and they chose the 4 best compounds for further study. Additional testing of one of the compounds, #43, revealed that it enters cells, where it directly inhibits palmitoylation of Shh. Consistent with Dr. Resh’s hypothesis, compound 43 also inhibits the growth of human pancreatic cancer cells. These features support the concept that compound 43 can be developed into an effective drug for therapeutic treatment of pancreatic cancer in patients.

Stimulated by the success of her Geoffrey Beene funded project, Dr. Resh is continuing to develop agents that target Shh into novel therapies. In collaboration with the Tri-Institutional Therapeutics Discovery Institute and Takeda Pharmaceuticals, we are developing drugs that work as Hhat inhibitors. To date, no other studies have used Hhat as a target in pancreatic cancer (or any other cancer), thereby making our approach innovative and unique. The Hhat inhibitors will be tested for their ability to block tumor growth in models of pancreatic, breast and lung cancer in the laboratory, and ultimately in the clinic.

Key Points:

- The abnormal expression of Shh(Sonic hedgehog) drives the growth of pancreatic cancer

- Dr. Resh planned to modify the abnormal expression of Shh by attaching a fatty acid, palmitate.

- After much experimentation Dr. Resh identified compound 43 as a compound capable of blocking Hhh action and pancreatic cancer cell growth

- Further development of compound 43 may lead to new treatments for pancreas cancer

Ross L. Levine, MD- Understanding the origins of myeloid malignancies

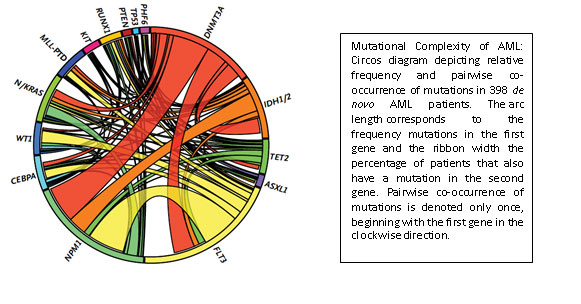

Ross Levine is another junior faculty member who was recruited to MSKCC through support from the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center. Acute myeloid leukemia represents an aggressive blood cancer for which new therapies are urgently needed. It is known that AML shows substantial differences in the genetic makeup and clinical behavior between patients. Work from MSKCC investigators and elsewhere has identified a poorly understood class of mutations that contributes to some forms of AML. These so-called “epigenetic” regulators do not directly impact the proliferation and survival of cancer cells but indirectly regulate other genes that do. Three of these genes are called TET2, ASXL1, and DNMT3A, and their inactivation occurs in a large fraction of AML patients.

With support from the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center the Levine group demonstrated these mutations influence the aggressiveness of AML. They then used these data to identify clinical implications of genetic alterations in AML, and to develop a clinically useful predictor that can predict overall outcome in AML and improve the ability of oncologists to decide on the best treatment strategy. As one example, their efforts identified certain subsets of AML patients that benefit from dose-intensified chemotherapy, which allows oncologists to reserve more toxic regimens from the patients for which this toxic strategy would be ineffective. Like the IMPACT assay, this work has led to the widespread use of mutational profiling of AML patients and to the development of state-of-the-art genomic profiling assays for patients at MSKCC and nationally/internationally.

Key Points:

- The Levine Lab performed comprehensive mutational profiling of the largest US cohort of AML patients.

- The Levine Lab identified specific genetic alterations that predicted the likelihood of cure or relapse after chemotherapy.

- The Levine Lab developed a novel, prognostic algorithm to show how genetic profiling can be used to predict outcome in AML, which is now in clinical practice.

Scott W. Lowe, PhD

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer in developed countries and, despite improvements in screening and early detection, it remains the second overall cause of cancer-related death. A goal of scientists in Scott Lowe’s Laboratory at MSKCC and the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center is to understand what genes are responsible for causing colon cancer to grow and spread in humans. This is because this information is essential for developing new, personalized and targeted therapies to cure the disease. Although many genes have been implicated to be colon cancer ‘drivers,’ perhaps the most important one is a gene called APC.

One function of APC in the colon is to control cell division. After cells in the colon have performed their job of absorbing nutrients, water and minerals from ingested food, they are shed after five days and replaced by new ones. This process is dependent on APC function, and mutations in colon cancer interrupt APC function. Therefore, colon cancer cells are not shed, and instead remain behind and grow in the colon as a tumor. If left untreated, this tumor can eventually gain additional mutations, causing it to invade surrounding tissues and distant organs.

To study APC, the Lowe Lab developed a unique system in which APC function could be turned off and on. They showed that when they turned off APC function, mice developed colon tumors that very accurately modeled human colon cancer. More importantly, when they restored APC in advanced tumors that were invasive, the cancer was completely eliminated and the mice were cured of their disease.

They confirmed these findings by studying colon cancer cells growing in petri dishes. Normal intestinal cells form organoids, or ‘mini-guts,’ in the petri dishes, recapitulating the process of cell division, cell shedding, and replacement by new cells. When they disrupted APC gene function in these mini-guts, this process stopped and the cells grew as a single large sphere, much like tumors in the mice. However, just like the mice, when they restored APC function in mini-gut organoids the organoids returned to normal.

These results are exciting because they demonstrate that correcting the specific defect in APC function can result in disease regression in animals that have colon cancer. However, there are currently no drugs able to do this in patients, but this work strongly suggests that further research to find such a drug may hold the promise to a more effective cure for patients who suffer from colon cancer.

Figure. Upper left: Normal colon tissue stained to identify proliferating cells (pink) in the “crypt” or differentiated cells (green) that are responsible for absorbing nutrients. Upper right: Colon organoids that recapitulate normal regions of proliferating and differentiated cells; Lower left: colon organoid with Apc off showing aberrant structures harboring only proliferating cells; Lower right: restoration of normal structures in organoids where Apc was off and then turned back on.

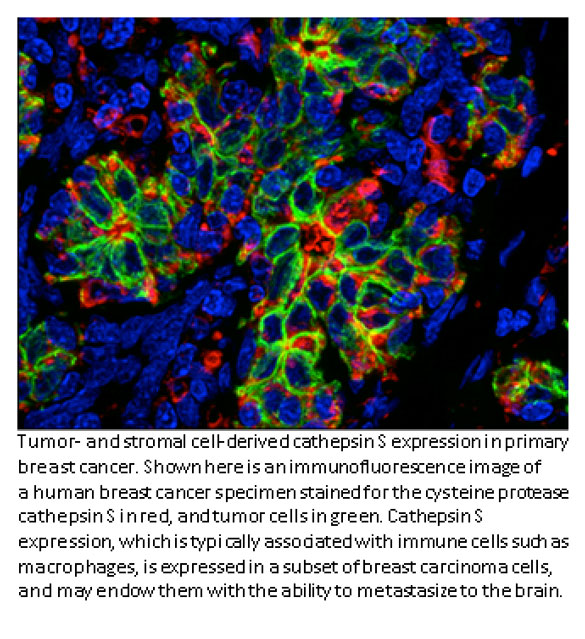

Johanna Joyce, PhD- Cathepsin S and breast cancer

Most cancer deaths occur when the disease spreads, or metastasizes, from the original tumor site to a distant location. In breast cancer patients, metastasis to the brain can occur months or years after seemingly successful treatment of the primary tumor. Johanna Joyce, an inaugural Geoffrey Beene Jr. Chair recipient and researchers at MSKCC have found that a protein called cathepsin S may play a key role in the spread of breast cancer to the brain. A complex interplay between breast cancer cells and certain surrounding cells called macrophages induces both cell types to secrete increased levels of cathepsin S, an enzyme that promotes the cancer cells’ ability to metastasize. Dr. Joyce’s lab recently showed that cathepsin S could be an important target for new drugs. The Joyce lab was interested in how these noncancerous cells at metastatic sites react when they encounter the tumor cells. To investigate these questions, the research team studied mice implanted with human breast cancer cell lines that are known to spread to the brain, bone, and lung. They looked at how both the tumor and its surrounding microenvironment change during cancer speading. The cancer cells and surrounding cells were subjected to genetic analysis to see which genes were more active than normal. In mice with brain metastases, the cathepsin S gene was significantly overexpressed. Interestingly, the tumor cells produced more cathepsin S at the beginning of metastasis and then tapered production, in parallel with a progressive increase in macrophage cathepsin S levels within the brain.

The researchers showed that cathepsin S enables the cancer cells to penetrate through the blood-brain barrier, a densely packed vascular structure that protects the brain from most large molecules in the blood. The researchers found that cathepsin S cleaves a protein called (JAM)-B, which normally helps hold cells in the blood-brain barrier together. The higher levels of cathepsin S presumably negate (JAM)-B’s effect and allow the cancer cells to penetrate the barrier.

To validate the role of cathepsin S in promoting brain metastases, the researchers inhibited it with experimental drugs. This significantly reduced the development of brain metastasis in the animals. The Joyce lab would like to move forward with clinical trials for cathepsin S inhibitors on cancer cells in the near future.

Key Points:

- Breast cancer patients are susceptible to metastasis to the brain after months or years of successful treatment of their primary tumor

- Cathepsin S may play a key role in the spread of breast cancer to the brain

- The research of the Joyce lab showed the cathepsin S enables the cancer cells to penetrate through the blood-brain barrier, allowing the cancer cells to penetrate the brain

- Experimental drugs were used to inhibit cathepsin S and this significantly reduced the development of brain metastasis in animals

Andrea Ventura, MD, PhD – ‘genome editing’

Structural changes to chromosomes have been known for decades to be common in human cancers. These rearrangements often result in the formation of gene fusions that produce cancer-causing capabilities. As these ‘fusion genes’ are not normally present in a patient’s cells, drugs that inhibit their activity can eliminate cancer cells without toxicities to normal tissues. Unfortunately, this type of mutation has proven very difficult to engineer in cells and even more so in model organisms and this has greatly limited our ability to investigate their biology.

Funds from the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center allowed Andrea Ventura to develop a novel strategy that allows the generation of virtually any chromosomal rearrangement directly in cells of adult mice and potentially other model organisms using a technique called ‘genome editing’ (Maddalo et al., Nature 2014, Vidigal and Ventura, Nature Commun, 2015). As a proof of concept for this approach, they generated a new mouse model of lung cancer caused by a chromosomal inversion that results in the generation a gene fusion known as of the EML4-ALK. They also showed that these tumors respond to chemical inhibitors of the fusion protein. Their innovative technology greatly expands our potential to make cancer models that accurately mimic the behavior of tumors in patients. Such models provide valuable pre-clinical platforms for evaluating new cancer drugs and testing strategies that overcome drug resistance.

Quotes from some of our scientists:

Director of the NIH and Nobel laureate, Harold Varmus, MD

Dr. Harold Varmus former chair of The Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center said, “the Center is dedicated to making revolutionary discoveries about how cancer works at the cellular level and using them for new approaches to diagnosis, treatment, and prevention.” Dr. Varmus adds, “The Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center has helped galvanize our efforts to gain new insights into cancer and to apply that knowledge to the development of more effective strategies for patient care. We are especially grateful to Tom Hutton and his colleagues at Geoffrey Beene, LLC for recognizing the significance of the work being done here.”

Andrea Ventura, MD, PhD